Genocide: the deliberate murder of a racial or cultural group.

On April 6, 1994, the plane carrying Rwanda and Burundi’s presidents was shot down. This double assassination of two ‘Hutus’ (the majority ethnic group in Rwanda) was the spark that ignited 100 days of massacre that left 800,000 Rwandans dead. They were mostly, though not exclusively, from the Tutsis ethnic group. During the following three months of insanity large numbers of the population perpetrated heinous crimes, including the rape of half a million women.

The skulls of some of those killed in Nyamata church during the Rwandan genocide.

Twenty years on, we have an opportunity to reflect on the genocide. Yesterday, Rwanda began a week of mourning and a series of events called ‘Kwibuka 20’ (Kwibuka means ‘remember’ in Kinyarwanda, Rwanda’s language). The restoration of Rwanda holds some beautiful lessons for communities rebuilding in the wake of conflict. In many ways the country has re-imagined itself during its painful healing process. Rwanda now has the highest percentage of women appointed to government of anywhere in the world, with women accounting for 64% of its parliament (in comparison America ranks 83rd with 18%). With a massive amount of hope invested in the potential of Rwanda’s youth, a big emphasis has been placed on education. The country has the highest primary school attendance in Africa, with 97% of children in primary school. The new Rwandan flag and national anthem reinforces the ideal of a unified country (though the fact that it is now illegal to talk about ethnicity in the country is not supported by everyone).

Voting in Rwanda’s 2010 presidential election. In the parliamentary elections last September, women won a majority of 51 out of 80 seats.

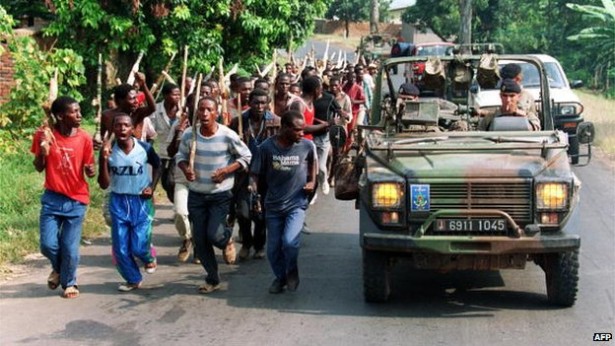

These are wonderful, hopeful lessons in restoration that many people in positions of authority across the globe seem willing to pay attention to. What is worrying, however, is that while there have been many professions of shame and promises to ‘never forget’ the genocide or let it happen again, we still don’t know how to respond quickly and appropriately to instances of extreme violence. The recent violence in the Central African Republic (CAR), where Séléka and anti-balaka have been killing innocent civilians, demonstrates that while we may be willing to remember the slaughter, we haven’t learnt from it. The same bureaucracy, perhaps even apathy, that prevented any meaningful intervention from western governments and the UN during Rwanda’s hundred days of hell remains king. While competing priorities including the crisis in Ukraine can account for some of the distraction of the world regarding the Central African Republic, the hard truth is that we have, to all intents and purposes, watched as thousands of people have been slaughtered, and over a million displaced. Yes, ‘watched’ is a strong word, but we now have access to more information than ever before regarding events happening across the globe. In comparison to the scant amount of information that was coming out of Rwanda during the genocide, at times it’s been possible to get live tweets on the situation unfolding in the Central African Republic. It is depressing that despite our access to more information than ever before, we’ve been unable to utilize it usefully.

Comparisons can be lazy, so it’s worth emphasizing that what happened in Rwanda and what is occurring in Central African Republic are different situations. However, the similarities are compelling. Like Rwanda, there have been individual tales of incredible courage and sacrifice and, like Rwanda, barring some intervention (in this case, from French forces and a struggling African Union mission) the Central African Republic has been abandoned. An EU peacekeeping force has been promised, but has yet to materialize.

In a passionate article, Simon Allison argues that violence in the Central African Republic shows that, twenty years on from Rwanda “we still don’t know how to curb humanity’s very worst excesses.” While this bleak diagnosis contains some truth, Invisible Children’s work to stop the LRA (a distinct mission to stopping anti-balaka and Séléka violence in the Central African Republic) is demonstrating that when we take action, we can take incredible steps towards peace. But it does take commitment, work and money – three things the international community seems unwilling to give to the Central African Republic.

During the Rwandan genocide, European soldiers were sent in to take European citizens caught up in the carnage to safety. They did nothing to stem the tide of bloodshed for Rwandans, a fact that becomes even more shocking given that some commentators believe that if these European personnel had combined with the small number UN force (soldiers from which were, unbelievably, withdrawn, reducing numbers from 2,500 to less than 300 after the violence began) they might have stopped some of the ensuing bloodshed. It’s the same philosophy of ‘looking after our own’ first and foremost that has prevented meaningful action in the Central African Republic – it’s just not a priority for governments when it doesn’t directly affect them or their citizens.

At Invisible Children, we believe that where you live shouldn’t determine if you live. It’s a guiding principle in our work in Central Africa dismantling the LRA from within and protecting vulnerable communities. As we join with Rwanda in remembering the genocide, we should celebrate the progress the country has made and courage of the Rwandans in pursuing lasting peace and prosperity.

However, rather than making empty promises of ‘never again’, we need to urge our governments and the UN to take action to stop further atrocities occurring in the Central African Republic.

(Photo credits: BBC, The Daily Beast, BBC)

Think people should hear about this?